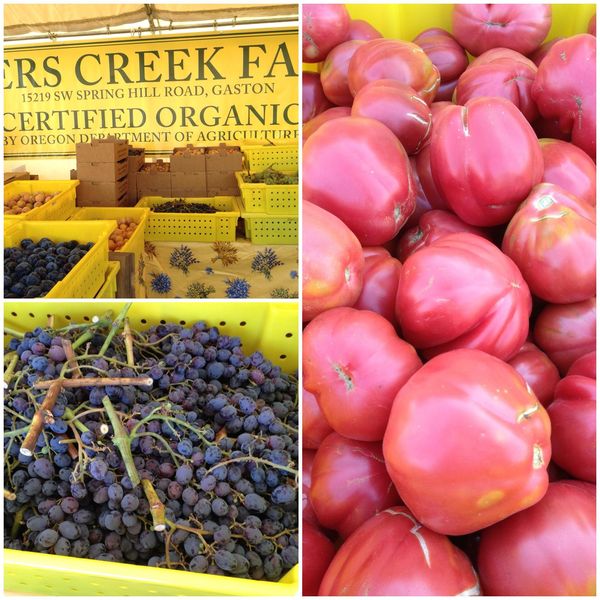

Ayers Creek Farm Newsletter September 28 2014 Market

Guest User

Verification I:

On the 18th of April our organic certifier visited the Ayers Creek for our annual inspection. Arriving at 9:30, he inspected our farm and our records without pause, finishing his closing interview at 2:15. Even though we have been through the process 15 times since 1999, it remains an intense experience. The application, submitted in March, articulated our organic farm management plan. After it was reviewed, an inspection was scheduled. The week before inspection, we make sure all of the records, seed packages, certifications and invoices are pulled together. All of the buildings, machines and fields must be open to inspection. The inspection fee is paid on the clock, so we try to make it as efficient as possible. No chit chat or lost keys, and niceties kept to the barest minimum. It is a serious matter because a cavalier decision or mistaken use of a substance will mean loss of certification of the crop or even the land for three years. By the time 2:15 rolled around, we were hungry and tired with a sense of evisceration. To our daughter who goes through the process at their Italy Hill Farm, we can say confidently that it never gets easier or smoother. We never talked to you about Santa either, did we?

Passing the review, inspection and audit allows us to carry the term "certified organic" on our labels and signs. Our second very important review and inspection comes when you all visit the farm on the ramble. We take it as seriously, and fret over details the week before. We are cognizant of the fact that if you are not satisfied with the way we farm, we could lose you as a customer. However, this inspection is much more comfortable because we can digress from the topic at hand and digest Linda Colwell's excellent food. This year's ramble will take place on the 12th of October, from 3:00 to 6:00 pm. Bring friends and family, along with sturdy shoes and a bee sting kit if you are allergic.

As a reminder, in our irrational New England Blue Law rectitude, we have kept the ramble strictly noncommercial. We won't be selling anything. Please don't try to lead us astray, just enjoy the stay.

__________________________

This Sunday marks our last market at Hillsdale until the 16th of November. By design, our fresh produce kind of peters out by the end of September and we need to spend the next month planting grains and garlics, subsoiling the berry fields and orchard as time permits, moving the irrigation pumps up from the floodplain, and pulling in the corn, sweet potatoes and squash. When the bell rings at 10:00 AM, here is what we will have.

More legumes: Borlotto Gaston, zolfino, purgatorio, Dutch bullet, tarbesque, chickpeas and favas.

More legumes: Borlotto Gaston, zolfino, purgatorio, Dutch bullet, tarbesque, chickpeas and favas.

Grains: frikeh, hulless barley, popcorn and cornmeal.

Some greens, tomatillos and onions again. With rain, tomatoes are iffy, but we will do our best.

A nice haul of table grapes, and maybe some prunes.

A nice haul of table grapes, and maybe some prunes.

Preserves. Finishing up the 2013 run. (When we return on November 16th, we will have close to a full complement, with some gift boxes as well.)

____________________________

Verification II:

This year, we will take a little over a ton of fruit, mix it with some sugar and fresh lemon, cook it up and put it into thousands of jars. Both Federal and Oregon laws mandate that we put a label on each individual jar. The law dictates what we put on the label and, as certified organic producers, we meet an additional set of label requirements under the National Organic Program. Labeling of processed food is neither optional nor voluntary. As really dinky players in the processing market, our labels cost more than the food giants, about 20 cents each, or around 3% of the jar's retail price. And it doesn't matter what we print on the label, the price per label mandated by law is the same. A simple fact.

This November, we will be voting for Measure 92 which adds the requirement that processors who use genetically modified ingredients must include that information on the already mandatory label. Same old label, just a bit more information. If it passes, processors like us will have a year to use up our old labels and print new ones that comply with the law. If, like us, they don't use genetically modified ingredients, nothing changes and we can use the old labels. Either way, adding a bit of text will not change the price of the label, nor the price of the food.

The state's shrinking tabloid of record managed to get into a lather over Measure 92. Shamelessly cribbing from the industry's talking points, and without a shred of critical thinking, the editorial board repeats the notion that this is a mandatory label. No, it is an additional bit of information on an already mandatory label. They also repeat the industry's claim that it will confuse consumers and increase food prices. Obviously, if an ingredient is from a genetically modified crop and the label says so, it is hard to see how the consumer is confused. The hysteria in the larger food industry has nothing to do with consumer confusion; it is the fact that they fear consumers will use that label information to select products made with non-genetically modified ingredients, and that it will force down the price of products labelled as genetically modified. Certainly, as we noted above, adding that language to the label will not add to its cost in and of itself.

Proponents of genetic engineering hold out the promise of crops that will grow nutritious food with little or no water, or fertilizer, offering up a seductive cornucopia of environmental and nutritional benefits. If that were reality, the food companies would be tripping over themselves with extravagant green claims on their labels, touting their genetic prowess in solving the world's problems. The promises have failed to materialize, as the most recent effort shows. Last week, the USDA approved the use of crops that are genetically engineered to survive the application of one of the first commercially available herbicides, 2,4-D, released in the 1940s. Why? Because farmers have sloshed so much glyphosate (Round-Up) across the nation's farmland that weeds have become resistant to the herbicide, so they are bringing back an old herbicide in hopes of stemming the tide. This is dirty old chemistry, and that is why the companies are horrified at the thought of a label underscoring this sad reality. They will slosh a cocktail of the chemicals over the farmland and then come back asking for approval of another herbicide resistance factor.

So you are narrowing your eyes and getting ready to dismiss us as working in our self-interest as organic farmers. Quite to the contrary, the status quo benefits us directly because we have the USDA seal of approval for our GMO-free status. When you see the NOP sticker or "Certified Organic" on a label, that means our seeds are not genetically modified, and that claim is backed-up with inspections and audits through the chain of custody. On the face of it, our support of Measure 92 runs against our self-interest. However if people want to know if their food is grown from genetically modified plants and animals, why not tell them so?

We will see you all Sunday, or for the Ramble on the 12th.

Carol & Anthony Boutard

Ayers Creek Farm