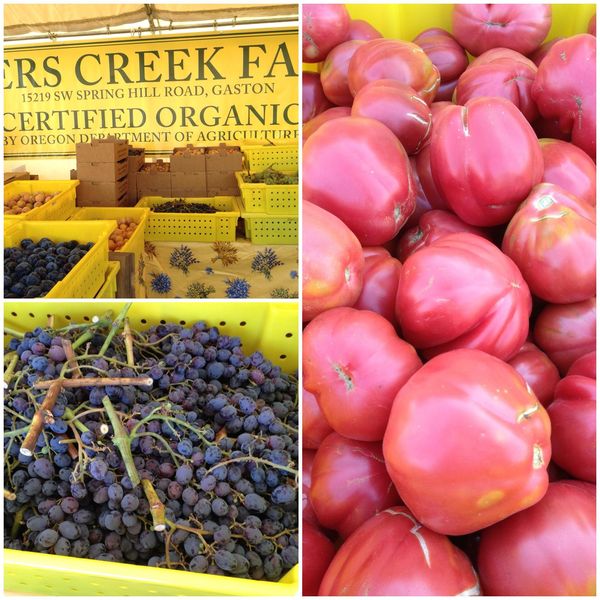

Ayers Creek Farm Newsletter August 23 2015 Market

Guest User

Goodbye Chester, Hello AstianaWhen the leaves display their autumn color, the bright yellows, oranges and reds appear because the green chlorophyll has been disassembled by the tree, and the other pigments in the leaf that have been there all along become apparent to the eye. This week there is a distinct shift in the flavor of the berries as the pectins and various flavor components in the fruit drop, and some of the more subtle flavors that were lost among the stronger elements are now out in front, the Chester's version of 'So Long, Farewell', or Hayden's "Farewell" Symphony, if you prefer the image of the performance ending on muted notes of the violin. Among the berries, this shifting flavor is unique to the Chester because of its long season, about five weeks in all. You can pick up the last of the season's now muted notes this weekend. We have posted our "Farewell Chester" letter to our buyers; strangely early and without the rain's coupe de grace that so often closes the harvest. This is the first time we have stopped before the school buses start.

Goodbye Chester, Hello AstianaWhen the leaves display their autumn color, the bright yellows, oranges and reds appear because the green chlorophyll has been disassembled by the tree, and the other pigments in the leaf that have been there all along become apparent to the eye. This week there is a distinct shift in the flavor of the berries as the pectins and various flavor components in the fruit drop, and some of the more subtle flavors that were lost among the stronger elements are now out in front, the Chester's version of 'So Long, Farewell', or Hayden's "Farewell" Symphony, if you prefer the image of the performance ending on muted notes of the violin. Among the berries, this shifting flavor is unique to the Chester because of its long season, about five weeks in all. You can pick up the last of the season's now muted notes this weekend. We have posted our "Farewell Chester" letter to our buyers; strangely early and without the rain's coupe de grace that so often closes the harvest. This is the first time we have stopped before the school buses start.

An oft repeated excuse for being "almost organic but not actually certified" rests on the unspecified cost of certification and the burden it creates for small farmers. Here is our actual out-of-pocket cost of certification for our dinky farm in 2015:

Application fee: $100.00

Inspection fee: 925.75

USDA Cost-Share: (750.00)

Total cost: $275.75

Since the adoption of the National Organic Program in 2002, the USDA has provided a cost-share program for farms going through the certification process. Among its strongest champions are our own Representatives Earl Blumenauer and Peter Defazio. We have been certified organic since 1999, back when it was fine to call a farm "organic" without any meaningful standards or inspections. Certification is never a cakewalk, and demands careful record-keeping and documentation of the farm's management. At times the details can be frustrating but never formidable; certification has made us better farmers. And, we will add as growers who bridged the two eras, the adoption of the national program has improved the quality of certification.

In our case, the cost difference between "almost certified" and certified is $275.75. The actual cost will vary from farm to farm, but it is a modest expense relative to other farm costs, not a crippling burden of thousands or tens of thousands as some farmers intimate. Gives Anthony an excuse to keep his flip phone and 56K modem so we have enough brass to cover that fearsome certification bill.

Another favorite excuse is that "you can't grow this or that crop organically." Is that so? Then Ayers Creek must be an ongoing failure as a farm because there are few crops we haven't grown over the years, all organically. We shun or drop crops because they don't work out with our current staffing, they don't make money, or in rare cases we find them simply boring, blueberries fit that category, not because they can't be grown organically. The first is the most common reason because, as Zenón and Abel will tell you, we are way over-extended and it is only due to their superhuman efforts that Ayers Creek doesn't collapse into a pile of rotten produce due to our vernal exuberance.

The 'Astianas' started ripening a couple of weeks ago. You missed them at the market because they never arrived. We ate all of them, savoring every single one; farmer's privilege. It is such a lovely fruit, an everyday workhorse of a culinary tomato, and we never weary of it. We will have a few crates full this week. Enjoy these first fruits fresh, in the grasshopper's moment, sliced and fried for breakfast, or in a fresh sauce with basil, fresh onion and garlic over some sort of pasta. As in the past, next week we will have the 20# bulk boxes for sale, and then you can kick in that Aesop's ant side of the brain and put them in jars. They will come in over the next three to four weeks.

We will also bring in the field run tomatillos. "Field run" is a trade term and means they are not graded according to size, color, &c. Pretty much everything we sell is field run. For the tomatillos, we selected out a diverse group of fruits for seed production, so it a good mix of types. Both tomatoes and tomatillos should be stored on the kitchen counter where there is good airflow. The tomatoes continue to ripen off the plant and, especially in Oregon, a few days on the counter finishes the flavor nicely. Our nights are a tad cool for tomatoes, especially in rural areas where the radiational cooling is stronger, and there is no concrete to store the day's warmth. We have had tomatillos last until March sitting in a colander. Peppers are better left on the counter as well.

We will have chickpeas and barley, and a few straggling packages of frikeh. We will bring in preserves again. Onions, garlics, tarragon. The beginning of the grapes.

Carol and Anthony Boutard

Ayers Creek Farm

_____________________________________

A personal note:

I grew up in a country where I was an untarnished citizen, even though my parents were immigrants. Courtesy of the 14th Amendment, the fact that I was conceived in another country and neither of my parents were citizens didn't matter a wit. I registered to vote and attended town meetings, and have never shrunk from participating in the messy business of government. Over the years, I have missed just one special election, even voting when the election involves just a handful of unopposed individuals and might be dismissed as unimportant. To the people who bother to get on the ballot the vote is always important.

Today, I am what the nativists call an "anchor baby,", a child born to immigrants but still entitled to citizenship. Or as some put it charmingly, a "child who was dropped in America." In fact, under the immigration rules in force back in the 1950s, my mother had to hide her pregnancy during the immigration interview or they would have been denied entry. Mother succeeded and I was born three months later, the first United States citizen in the Boutard tribe.

For the last 17 years, I have had the pleasure of working with a variety of immigrants whose children were born here, and are citizens in the fullest meaning of the word. Like me, their children had no choice regarding the location of their conception or birth. Unlike me, they are having their citizenship called into question at a critical time in their lives. Fifteen years ago, I was brought up short by a 16-year old woman who, when I asked for her resident alien card, snapped back that she was a citizen and provided her passport. I apologized for my assumption and smiled explaining that my parents also carried resident alien cards, easing the tension. Since then, my assumption has changed. The truth is that both of us knew that no one ever assumed I wasn't a citizen. I have registered to vote in four different states and no one has ever asked for proof of citizenship, even though as a child of immigrants I bear a touch of accent. And when I was a youngster, no one ever told me I wasn't welcome in this country because my parents were aliens.

Children of immigrants from non-English speaking countries encounter a special challenge. They often have to serve as translators and intermediaries for their parents. This is true whether their parents come from the Ukraine, Poland, Japan, Vietnam, Sierra Leone, Iran or Mexico. They are a fragile bridge between their parents and everyday life, between two spheres of authority. They translate contracts, fill in forms and roll with the patronizing English-speaking adults. They should earn our praise and support, a kind word not our petty slurs.

One of Francois Truffaut's later films, Small Change (link), deals with the travails of children in society. He deftly and humorously examines the callous way we treat children and the affronts they suffer at the hands of adults. The fact that our political discourse has dipped back into the wallow of "anchor babies" is very dispiriting, and underscores Truffaut's point that we crap on children all too often and all too easily.

Anthony